A farm known in the Great War as 'Pondfarm' by the British Forces, and as 'Kazerne Häseler' by the Germans.

The origin and war history of Pondfarm:

On 2nd November 1914 the population of the village of St. Julien were ordered by the municipal authorities to leave their homes and the village. The inhabitants of the Northern and Eastern sides of the village could already see the German troops advancing while German bullets were zipping around.

At about noon, the exodus started from the village towards Ypres or surrounding villages where people had relatives or friends living.

Many people thought they would only be away from home for a few days, so they left most of their possessions at home. They were as good as certain of a swift return.

The following night the opposing armies engaged in battle. A return home for the people of St. Julien became impossible.

Below: a photo of " Kazerne Haeseler", which was the German name for Pondfarm.

(This photo shows the farm Arsène Marant left in May 1914.)

Changes of occupying forces:

- 1914: British forces (see the book: Ieperboog, Slagveld België 10)

- 1915: At the start of the first gas attack (Steenstraet), Pondfarm was the headquarters of the 2nd Canadian Infantry Brigade.

- 1915: German forces.

By July 1917 the German Army had reinforced their bunkers and their (defence) lines with underground tunnels. Several farms, including Pondfarm, thus became real small fortresses. At Pondfarm three large German bunkers of about 40m length (43 yards) were located, as well as a number of smaller bunkers, underground tunnels and cellars. A narrow-gauge railway, located just behind Pondfarm, was used for transporting most of the material and equipment to these bunkers (see main page).

- 27th April 1917: German forces

- 31st July 1917: British forces, German forces for a couple of days

- 8th August 1917: British forces

- 22nd August 1917: British forces, 2/5th Gloucestershire Battalion (see below).

- 28th September 1918: Belgian forces (the 1918 Belgian offensive defeated the Germans

definitively)

Further information concerning this Lieutenant-Colonel is not available, nor is the source of this information.

On 22nd August 1917 the 2/5th Gloucestershire Battalion was involved in an attack, part of the Third. Battle of Ypres, on Pondfarm and captured it. This resulted in 3 officers and 16 Other Ranks killed, also 1 officer and 51 Other Ranks wounded, and 1 Other Rank missing (2/5th Gloucestershire Battalion War Diary).Their Commanding Officer at the time was Colonel Collet.

The 3 officers who were killed and who are mentioned in the "Roll of Honour" of Officers of the Gloucestershire Regiment were:

DAVIS, Sidney Alfred, 2nd Lt., aged 25, died 22nd August 1917.

TUBBS, Seymour Burnell, Capt., aged 28, died 22nd August 1917.

BLYTH, Alick Frederick, Lt., aged 20, died 23d August 1917.

Their names are recorded on Tyne Cot Cemetery Memorial to the missing.

The names are also on the Remembrance page of this website.

The first family that took the risk of returning to the village of St. Julien arrived there on 14th January 1920. The rest of the inhabitants followed slowly later on.

Everyone who had the courage to start a new life here really had to perform pioneering work. In the first period of reconstruction, Cyriel Petillion and Arsene Marant learned from the mayor and secretary of Langemark that the parish borders were going to be changed. Part of the parish would be allocated to Langemark, another part to Zonnebeke. As a result of this, many people chose to resettle at Langemark. Cyriel and Arsene then started a petition to the local bishop, asking him to retain the parish of St. Julien within Langemark. All the inhabitants signed that petition. The bishop of Bruges agreed and granted the request of the people of St. Julien.

Before the war, Arsene Marant lived at a farm called 'Prinsenhof', known in the war as Border House. This farm belonged to the same owner as Pondfarm. After the war, the farmer of Pondfarm (like so many others) didn't return to his farm. Consequently the owner of the farm(s) decided to reconstruct only one farm: Pondfarm.

The local authorities worked devotedly for the cause of the reconstruction of their demolished towns. This was far from an easy matter. Even though several funds had been established by the government, things didn't work out that smoothly due to bureaucracy and shortage of materials and finances. Still people, from time to time, received some loans for the reconstruction and compensation for the war damage they had suffered. Help in kind, such as cattle, tools and farming equipment could also be obtained.

The boundaries of the Pondfarm property were marked out by Arsene Marant using plough and horse. In the beginning they constructed a wooden barrack for housing, using timber they found in the area. Later on a proper house was constructed with home-made bricks. Those bricks were quite irregular in shape and form. Due to the stove used inside the house, a number of bricks got blackened. After these first buildings went up, a new house and farm arose. The first little brick house was then used to accommodate the farmworkers.

Before the war, the 'Roeselarestraat' (street to Roeselare) was laid with cobble stones. Due to the shelling in the war, the road was quite damaged. There were a lot of potholes, and in some places timber had to be placed in order to make it passable.

Just after the war, piles of copper shell-cases as high as a house could be seen here. Possessing copper was prohibited. It was too valuable a material.

All those copper shell-cases were removed by the authorities. Even after that, police officers in civilian clothing patrolled the area to prevent the stealing of copper or to arrest those caught in the act.

Setting the fields alight was a technique used to clear the area of explosives, particularly bombs just below the surface. It was as if the war had started again.

The day after each fire, the shells would be removed. The weather also created some problems, as in the summer of 1921. Temperatures were so high that summer that shells and bombs in uncleared areas exploded due to exposure to the heat. The nearby 'Fortuinhoek' (Fortune Corner) was an area where this happened more than once.

The grounds of the nearby Gallipoli farm, after the war, remained fallow. It was therefore used for storing munition and as a detonation area. Bombs containing gas were also frequently set off there. When the wind blew in the direction of the neighbouring houses, the gas also drifted that way. The neighbours then had to gather around the fireplace in their homes because the fire dispelled the gas.

Removal of war ammunition was mostly done by workmen from outside the region. They were paid according to each square metre that was cleared.

The material they had collected was supposed to be officially collected and deposited, but still some material escaped from the official depot and was secretly sold to local people. Copper and iron were valuable and wanted.

Some workmen, local people too, also tried to dismantle the munitions, secretly on their own. This was an illegal activity and a very dangerous one as well. Some men got severely wounded, and some even died as a result of exploding munitions. Such terrible events even occurred many decades after the war.

After the war, the search for, and the trading of, war relics turned out to be a profitable enterprise for the local people too. A good sum of money was earned this way, producing a real and major income. The farming and cultivating of the farmlands was a secondary job in those early post-war days. Only after the land had been sufficiently cleared could farming begin again. Up to about 1923 oats, peas and beans were the only plants that were cultivated.

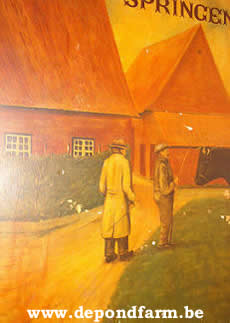

After the war, many people were convinced that it was going to be impossible to rebuild the village and cultivate the land again. Taking into account the total destruction and devastation they saw before their eyes, it isn't hard to understand their view. Still, it turned out differently as, year after year, the normal way of living resumed. As mentioned before, a lot of inhabitants made good, profitable living from trading war material. This (modest) prosperity was noticeable in the growing number of new cafés. One café, called "De Barrière", had a painting by Achiel Ghyselen showing the whole front area. For the wall of the new Pondfarm, the same artist made a painting of that farm as well.

It took a long time after the war before 'Roeselarestraaat' (street to Roeselare) was repaired. At the time the street was made out of cobble stones. In view of continual subsidence, the cobble stones were removed and the street was completely renewed. Most of the cobble stones were purchased by the residents.

Here and there the original cobble stones can still be found in the area. At our Pondfarm, for example, there is a small pathway made out of them. If those stones could talk ... what war time stories they could tell us!

Even nowadays a lot of war material is still being found. Metal, iron objects which are embedded in the ground, only rises to the surface over time. After a wet season the number of objects that surface is more numerous, and the months of October (when potatoes are lifted) and April (after ploughing) see the greatest quantity of war materials coming up.

Munitions, bombs and shells from the war that had been found used to be collected 2 or 3 times a week by the special military service (at Houthulst). Nowadays we have to contact the local police. They first come to check and verify the finds. The military service eventually collects it later on. Since 2003 the local police have been responsible for making reports of the finds. We have obtained permission to make a yearly declaration of our finds, so in this way we're able to take photos of our "treasures" year by year.

Photos below:

- label that describes the finds: sort and amount, place where things are deposited.

- the Special Military Service collecting the finds at our place.

(English translation Frank Mahieu and Roger Joye)